Printing labels for very small production runs of rapidly evolving hardware

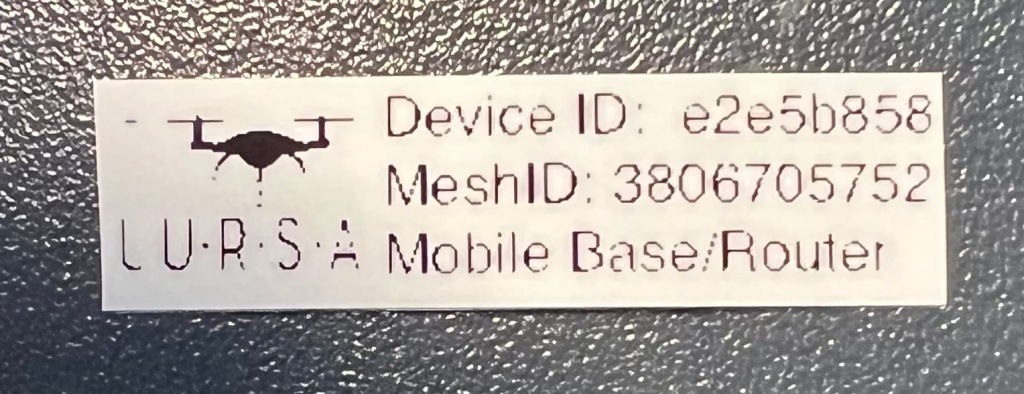

We are developing a small hardware device that consists of ESP32 development boards (~$50), 3D printed cases (~$3?), padded electronics cubes from Amazon (~$15), and a very light touch manual. Everything is rapidly evolving but since we want to track each device, we need to put a label on it with its MAC address and another identifier. And, if we’re going to go this far we might as well put a logo on there as well.

ptouch-print

Command line utility to send text and graphics to some of the Brother P-Touch label printers. I started with this MacOS fork: https://github.com/DavidPhillipOster/ptouch-print-macOS

This runs nicely on OSX but the various sites he references for the original source and documentation have vanished. This site offered the necessary instructions for using it effectively: https://github.com/HenrikBengtsson/brother-ptouch-label-printer-on-linux

To combine a logo and text you need to make them both into PNG files and then print them both with a bit of padding between them. This also allows you to print multiple labels by stringing PNGs together.

From a workflow perspective this actually works quite well. Unfortunately the resolution of the label maker is rather poor.

It would be easy to write some Python to read the values from a CSV file and create all the labels I need in one pass.

Dymo LabelManager 420p

This is a handheld label maker with a alphabetical rather than QWERTY keyboard. Since I’ll rarely be typing on it, the keyboard isn’t an issue.

I’m driving this with Dymo’s “Dymo Connect” software. It has very simple layout capabilities for text, barcodes, QR codes, and images. For my purposes, I put a logo and three lines of text into the layout, hit print, and received a decent label.

I’ve not investigated to see if I could drive this from a spreadsheet to partial automate the process. For low production volumes I am OK with copy/pasting the information for each label.

Still rather pixelated but a bit crisper than the Brother. This is what you get with 180 dpi.

blabel

https://github.com/Edinburgh-Genome-Foundry/blabel

This was the first recommendation for something that might meet my requirements. Command line driven, written in Python, can ingest CSVs to produce multiple labels, basic layout capabilities via HTML and CSS style sheet.

It was a bit clunky to get working and I think we found a CSS layout problem but we eventually got it to reliably produce PDF files. But, what do I print these small PDFs to? I think I’d need yet another label printer, one that took PDFs.

Present and Future

Ultimately, we need a higher resolution printer that can print to pre-cut waterproof (thermal printed plastic). But for the moment, the Dymo is good enough.

Other Options

I tried or thought about a few other things:

- 3D printing the logo and identifiers directly on the case

- This would be hard for just in time assembly

- The available space is on the side of the case. We need to print the case lying on the top so the sides would be vertical. Printing fine text one layer at a time gets pretty ugly.

- Various forms of printing to sheets of labels

- I’m building 1-5 devices at a time. Populating the template and taking into account already used labels on the sheet was a bit annoying.

- Waterproof (plastic?) labels in sheet form were not easy to find

A Crowd Sourced Non-Fiction Reading List

I read a -lot- of fiction, and was feeling guilty about it. “I should be expanding my awareness of the world!”. (Rather than taking care of my mental health by reading novels for pleasure that allowed me to escape for hours on end….)

Part of the issue is that my recent efforts at reading non-fiction resulted in quickly losing interest and abandoning the book 25% of the way through. What to do, what to do?

Crowd source it. I’ve a fairly eclectic group of friends and the list below reflects that. I’ll add personal commentary as I finish a book, otherwise it is just title, author, and maybe a quick comment.

Please feel free to suggest additions!

Books I’ve Read and Recommend

- Guns, Germs, and Steel – Jared Diamond

- I read this years ago and was captivated. It read like a world and time-spanning novel. It was a great and memorable read.

- There are discussions about the validity of his approach which may be worth reading. Here is one – https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/wd6jt/what_do_you_think_of_guns_germs_and_steel/

- Devil in the White City – Eric Larson

- “Bringing Chicago circa 1893 to vivid life, Erik Larson’s spellbinding bestseller intertwines the true tale of two men–the brilliant architect behind the legendary 1893 World’s Fair, striving to secure America?s place in the world; and the cunning serial killer who used the fair to lure his victims to their death. Combining meticulous research with nail-biting storytelling, Erik Larson has crafted a narrative with all the wonder of newly discovered history and the thrills of the best fiction.”

- It lives up to the quote on the inside flap. Go read it.

- A Walk in the Woods – Bill Bryson

- I read this in my … 30s, I think … after spending a few years living in New England. His books are -fun- and captivating and educational.

- In a Sunburned Country – Bill Bryson

- The Story of Sushi: An Unlikely Saga of Raw Fish and Rice – Trevor Corson

- I read this shortly after finding really good sushi in San Francisco. It tells two stories – the story of sushi’s history and the story of sushi in America. A good read for foodies, and for sushi lovers.

- The Secret Life of Lobsters: How Fishermen and Scientists Are Unraveling the Mysteries of Our Favorite Crustacean – Trevor Corson

- A wonderful dive (get it?) into what the title says. A well researched story about something we think we know, but really do not.

- Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!”: Adventures of a Curious Character – Richard P. Feynman , Ralph Leighton , et al.

- I read this many years ago and remember it fondly, though I do not recall any details of why. Go discover “why” for yourself.

- Any Given Tuesday – Lis Smith

- She is a Dartmouth graduate, though was there after I left. She is also a political operative of the first order. Her character could have appeared on West Wing and fit right in with the passionate characters who believe in sacrificing much for “Democracy”. A great read.

- The Objective in War – Capt. B.H. Liddell Hart

- I downloaded this paper just to find the context for the quote: “The object in war is a better state of peace.” I stayed because it was a very interesting read, and one still (or perhaps more) relevant now than when it was written in 1952. Among other things, it carefully de-mythologizes Cluasewitz (the author of “On War”) but it also covers the differences between political objectives and military objectives, military vs civilian (or infrastructure) targets, and why you might not want total victory. It is a short and quite readable paper, very much worth the time.

- Enough – Cassidy Hutchinson.

- I’m listening to this as an audiobook. This is a superb first hand account of how our government functions from a first person view just before and then during the Trump administration. Cassidy comes off as incredibly capable, driven, and idealistic all while neatly avoiding even a hint of egotism. Very worth reading.

- Danziger’s Travels – Nick Danziger

- I read this many years ago and it may have inspired me to read more “adventure travel” books, and to do some of it myself. Beautifully written by a guy who “… With minimal equipment and disguised as an itinerant Muslim, he hitch-hiked and walked through southern Turkey, and the Iran of the Ayatollahs, entering Afghanistan illegally in the wake of a convoy of Chinese weapons and then spent months dodging Russian helicopter gunships with the rebel guerillas. He was the first foreigner to cross from Pakistan into the closed western province of China since the revolution on 1949.”

- The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia – Peter Hopkirk

- A must read for anyone interested in what is going on in Central Asia and parts of the Middle East. To quote a review: “The Great Game between Victorian Britain and Tsarist Russia was fought across desolate terrain from the Caucasus to China, over the lonely passes of the Parmirs and Karakorams, in the blazing Kerman and Helmund deserts, and through the caravan towns of the old Silk Road—both powers scrambling to control access to the riches of India and the East. When play first began, the frontiers of Russia and British India lay 2000 miles apart; by the end, this distance had shrunk to twenty miles at some points. Now, in the vacuum left by the disintegration of the Soviet Union, there is once again talk of Russian soldiers “dipping their toes in the Indian Ocean.”

The As Yet Unread Reading List

- Sapiens – Jared Diamond

- Collapse – Jared Diamond

- 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus – Charles C. Mann

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants – Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Gathering Moss – Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Redeployment – Phil Klay. Short stories on the military. “Incredible”

- Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation – Kristin Kobes Du Mez

- Preparing for War – Bradley Onishi

- How Civil War Starts – Barbara F. Walter

- Zero Fail – Carrol Lenning

- Inside Delta Force – Eric Haney

- The Federalist Papers

- Palenstine – Jimmy Carter

- Red Notice – Bill Browder

- Freezing Order: Freezing Order: A True Story of Money Laundering, Murder, and Surviving Vladimir Putin’s Wrath – Bill Browder

- The Red Hotel – The Red Hotel: Moscow 1941, the Metropol Hotel, and the Untold Story of Stalin’s Propaganda War – Alan Philps

- Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation – Joseph J. Ellis

- Preventable – Andy Slavitt

- The Breach – Denver Riggleman

- Blowback – Miles Taylor

- Enough – Cassidy Hutchinson

- Shattered Sword – The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway – Jonathan Parshall, Anthony Tully, et al.

- Moon Lander – Tom Kelly

- Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI – David Grann

- Innovators – Walter Isaacson

- Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History – Sidney W. Mintz

- The Prize – Daniel Yergin

- Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World – Mark Kurlansky

- Salt: A World History – Mark Kurlansky

- The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance – Henry Petroski

- 52 Loaves: One Man’s Relentless Pursuit of Truth, Meaning, and a Perfect Crust – William Alexander

- The River and the Gauntlet – S.L.A. Marshall

- The Wordy Shipmates – Sarah Vowell

- Unfamiliar Fishes – Sarah Vowell

- Lafayette in the Somewhat United States – Sarah Vowell

- Assassination Vacation – Sarah Vowell

- The Church of Baseball – Ron Shelton

- Reading the Glass: A Captain’s View of Weather, Water, and Life on Ships – Elliot Rappaport

- Wilding – Isabella Tree

- The Wager – David Grann

- Guardians of the Trees: A Journey of Hope Through Healing the Planet: A Memoir – M.D. Webb, Kinari

- Fire Weather – John Vaillant

- The Pyrocene: How We Created an Age of Fire, and What Happens Next – Stephen J. Pyne

- Anything by John McPhee – (Start with The Founding Fish)

- Anything by Thomas Sowell

- The Aviators – Winston Groom

- Isaac’s Storm – Erik Larson

- Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania – Erik Larson

- The Good Soldier Schweik – Jaroslav Hašek (Possible source for Catch 22)

- The Edge of the Plain- How Borders Make and Break Our World – James Crawford

- A Hawk in the Woods – Carrie Laban (Deeply creepy)

- Endurance. The Ernest Shackleton Story. (Fabulous tale of will to succeed and commitment as a leader.)

- Twilight of Democracy – Anne Applebaum (Not very well written but at only 95 pages, worth reading)

- Add these – https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2023/11/how-technology-building-plane-engineering-works-books/675905/?utm_campaign=atlantic-daily-newsletter&utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=20231111&lctg=6050e71e4953a53f14887553&utm_term=The%20Atlantic%20Daily

SAR UAVs: Video examples of IR, optical, and other challenges

We are working on developing a program for UAVs for SAR in NH. Part of this effort involves evaluating and selecting appropriate sensors. Another is “simply” figuring out what works, what doesn’t, what the use cases are, how to meet those use cases (if we can), ….

We’ve done a lot of scenario work and put together some videos to illustrate some of the challenges SAR UAVs face.

- Successful IR find. Subject was on edge of the tree line, early in the day, away from the sun so the ground didn’t have a chance to warm up. As you can tell from the optical view, the subject probably would have been located via an optical sensor as well.

- Unsuccessful IR find. Subject was just inside the tree line and hard to detect with an optical sensor, one of those use cases where you want IR to work. But it was late morning on a ski slope that was in full sun for a few hours and the human’s heat signature gets lost in the clutter.(The subject appears in both 50 second video clips, and you know that they’re present. Now imagine that you’re looking at this in real time after flying for fifteen minutes. How likely are you to detect the subject then?)

Searching in real time with a UAV is hard. You must fly a slow, methodical flight path to get decent coverage. Conditions must be in your favor. The sensor operator must be trained to look for clues and, if you are using IR, the sensor operator must have experience interpreting IR imagery.

See the end of this video for another example of searching with an optical sensor.

In most cases, I think that searching with a UAV will either be a initial search (aka points and routes) or a post flight image review mission to get decent PODs.

Demonstrating Some UAVs for SAR Challenges

We’re developing a UAV program for SAR in New Hampshire. Lots of things “in flight” on this. Some recent posts:

We are flying a lot of training scenarios. Educate the canine handlers, develop use cases, evaluate software, evaluate hardware, develop SOPs, everything.

I am sharing the following video from a recent training session to share some of our findings in an informal manner and to hopefully encourage others to do the same.

(If you are in New England and working on a UAV program for Public Safety, please contact me and I’ll add you to the New England Council for Public Safety email list. If you are elsewhere, I encourage you to join the National Council.)

Visual demonstration of requirements:

1) Really need a “go to UTM (or lat/long)” capability. The handler was under a tree and finding her was the first problem.

2) Seeing anything on a small screen is hard. I missed the ripples while flying. During playback, they clearly indicated where the handler was.

3) Need communications protocol. She was trying to guide me to a clue. Right, left, et al aren’t clear. River left only makes sense to river situations. (IR illuminators?) We did have radio comms but without a VOX mic, that slowed the process down.

4) Need strobes on the handlers to quickly locate them.

5) I am right over a pink Croc. Did you see it? I certainly did not until later.

Additional challenges, with narration:

A lot of people ask me about search patterns, height, detection capabilities, etc. I figured I’d just share this video and narrate it to show, in real time, some of the challenges I was facing.

Note: This is all done with a Mavic Pro. Other (more expensive) platforms will address some of these issues.

How to (Tactically) Succeed

I’ve had an insanely productive week – hired two people, built three antenna masts, built one “go kit” for SAR/EM communications, moved two wildly different critical projects forward, identified an issue in another organization and the person who could help us fix it, sealed and caulked a bath tub, …. You get the idea.

And so, after getting even more stuff done this Saturday morning (identifying RF issue affecting radio power supply, fixing it, sorting out various cables that need to be in that kit), I decided to pause and figure out WHY I’d been so productive.

I thought about the various projects, consciously and subconsciously, long enough to mentally ensure that everything was in place to accomplish the goals.

Looking back, what usually blocks me from completing a project is my failure to have the right resources – tools, components, people, software packages, whatever – available to get the job done. I’d get part way into the project and would be forced to stop while I located the missing resource. And once stopped, I stayed stopped because something else was there that I needed to accomplish. (Squirrel!)

This approach creates some semblance of chaos in the form of bits of random gear on the floor, or lots of tabs open in my browser, or an online shopping cart populated but not purchased. But when my mind says “Let’s go!” it seems to be triggered by a subconscious awareness that everything is in place to go, and to finish.

These were all tactical successes, but if you fail tactically too often, you are unlikely to achieve strategic success.

Rapid deployment of SAR UAV

We are working on developing a SAR UAV program. This includes SOPs, use cases, equipment load outs, software, training, everything.

As part of the R&D effort, I’ve been working on building our the UAV equipment kit to determine what is required, what is desired, what works, what fails, how to pack it, etc.

This video demonstrates our ability to transition from hiking to flight operations in two minutes, including the time required to remove the gimbal lock that I always forget.

The end of the video also shows some of our operational challenges, in this case finding a launch site and very dense foliage. I had to zig zag my way up. (And back down, which was more “interesting”.)

And, a drone’s eye view of the same operation.

Mavic Pro kit for search and rescue operations

I am assisting a local agency with developing a SAR UAV program. Among other things, we will develop use cases and their attendant requirements to drive platform selection but for the moment we’re using DJI Mavic Pros.

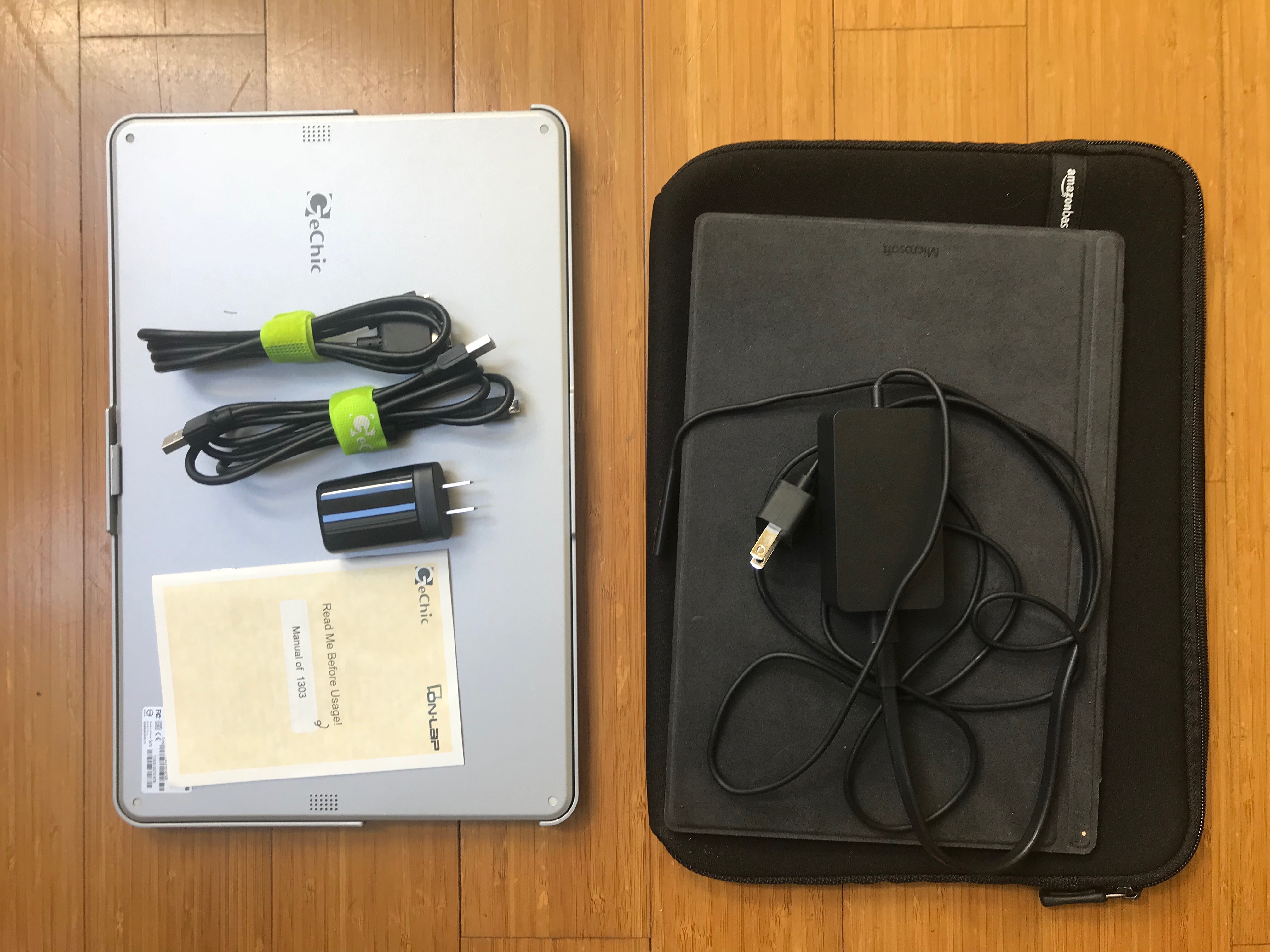

What follows is my working UAV SAR kit built around the Mavic Pro.

Each component of the kit will be discussed in more detail below. Clockwise from the upper left we have:

- Lightweight HDMI external monitor, USB or 12V DC powered

- Microsoft Surface Pro

- Molle water bottle carrier (repurposed as a Mavic carrier)

- Semi-hard shell Mavic case

- Dedicated phone, external battery, cables, and spare props

- Dual radio harness with type approved VHF radio, type approved air band radio, GPS

- Rapid parallel battery charger, 12V “cigarette lighter” charger

External data viewing and processing

The kit includes a Microsoft Surface Pro running Windows 10. It doesn’t really have enough power to run Pix4D (for example) but it is sufficient for some in-field image processing. It can also run Mission Planner for PixHawk enabled UAVs and can serve as a backup data storage device.

The item on the left is a very inexpensive, lightweight, USB powered HDMI screen. The Surface Pro drives it quite well. We need to determine is the Mavic controller can.

Molle Mavic carrier

This is a molle water bottle carrier with a large semi-padded main compartment, a zippered front pouch, and a zippered lower pouch. The Mavic Pro fits snugly in the main compartment with room for a spare battery below it in that compartment. A second spare battery fits in the lower zippered compartment. Cables, phone, and other small items fit in the front compartment. There is no room for the controller but we will attach another molle bag to the side of this carrier to hold the controller.

This would be the bare minimum kit and could be strapped to other gear or carried on its own.

Semi-hard shell Mavic case

There are lots of Mavic cases out there. We went with this one because it has room for three spare batteries, the foam is laser cut rather than pick and pull, and the case is semi-rigid.

We also added prop clips (white item over Mavic) to hold the props in place when using the molle carrier, a controller stick guard (lower right, black) to keep the sticks from moving or being damaged when not in use, and a phone mount that moves the phone above the controller and allows for phones in hard cases to be used.

Dedicated phone, external battery, cables, and spare props

All SAR flight operations must use a dedicated mobile device rather than a personally owned device. This limits exposure to malware, keeps potential evidence on a device owned by the organization, and provides for consistency across kits. This happens to be a Galaxy 8, chosen for maximum screen brightness.

Also included here are an external battery for recharging the phone, a charger for the phone, spare props, and spare cables.

Dual radio harness, radios, GPS

The UAV operator needs to be able to communicate with others involved in the response and also with other manned and unmanned aerial assets. The kit includes a type approved VHF radio for response communications and a type approved air band radio for air operations. (The pilot program lead operator has a ham license (not required for this equipment) and manned aircraft ratings.)

Also included is a GPS unit. The team normally uses Garmin Alpha 100’s which automatically transmit on MURS frequencies to enable base to track assets in the field. To limit potential sources of interference, this GPS unit is passive and does not broadcast.

Rapid parallel battery charger, 12V “cigarette lighter” charger

The standard Mavic battery charger is serial – it charges one battery, then the next, then the next. Charging three batteries can take upward of four hours. This charger will charge three batteries and the remote controller in parallel, dramatically improving available flight time.

The stock 12V cigarette charger is included to go out with the molle carrier kit.

And that is the working draft of our basic Mavic Pro SAR kit.

Questions, comments, and feedback are most appreciated.

How to succeed as a startup

Book, in Firefly, once said “Out here, people struggled to get by with the most basic technologies; a ship would bring you work, a gun would help you keep it. A captain’s goal was simple: find a crew, find a job, keep flying.”

The startup version is:

“As a startup, people struggle to get by with the most basic resources; an idea will bring you attention, passion will help you keep it. A founder’s job is simple: build a team, find revenue, survive.”

Guidance to UAV Operators Responding to Florida

[I am the Public Information Officer for National Council on Public Safety UAS. This post is written in that role. We will stand up an official location for future announcements.]

The Director, Emergency Management and Homeland Security Program, FSU, working in conjunction with local, state, and Federal agencies, requests that all volunteer UAS operators respect the following:

Volunteer/humanitarian aid/emergency response operators:

- Do not self-deploy during response/life-safety, it’s dangerous.

- Register on volunteerflorida.org.

- When the State gets to recovery, we will need help. Registered volunteers should report to a Volunteer Reception Center for vetting and assignment.

- Be prepared to be self sufficient. Do not assume that food, shelter, water, transportation, power, medical support, and fuel will be available to support your activities

Commercial operators:

- All commercial operators working for utilities, insurance companies, etc should comply with their Part 107 restrictions.

- Please coordinate operations through local and state EOCs if flying during response phase.

Official agencies:

-

Official agencies should contact the FAA Systems Operations Support Center (SOSC) at 202-267-8276 and request an Emergency COA or SGI. This authorization will permit operations inside any posted TFRs or within controlled airspace.

All operators in Florida should utilize Airmap (including registering of flights) for maximum visibility. Emergency Management is using Airmap to help deconflict air operations.

Other guidance:

- Low flying aircraft will be an issue.

- Monitor FAA and other resources for new or changing TFRs.

- Follow the eCOA process when working with a sponsoring agency or private sector partner.

- Be patient with the SOSC as they will get bombarded with requests

Defending Against UAVs Operated by Non-State Actors

The author hopes to help the reader understand the potential impact of consumer UAVs in the hands of non-state actors as well as the technical and regulatory challenges present in the United States that we face so that they can make informed decisions about public policy choices, investments, and risk.

Our hypothesis is that Western nations are not prepared to defend civilian populations against the use of small UAVs by non-state actors. This can be proved false by:

-

- Identifying counter-UAV technology that can be deployed to effect a “win” against currently available UAVs that meet the UsUAS definition

- Identifying the regulations that allow the technology to be utilized within the borders of the United States and at sites not covered by “no fly zones”.

- Demonstrating that the solutions are capable of being deployed at sufficient scale to protect all possible targets, not just major events

The defenders are at a classical asymmetric warfare disadvantage – they need a nearly 100% success rate, and if they can demonstrate that success, even better. This is essentially an impossible victory condition to meet. If the scope is limited to critical infrastructure, and if the rules of engagement are adjusted, the odds increase dramatically for the defenders but are still daunting.

Attackers win if they can conduct a single terror attack using a UsUAS against any civilian target, one of thousands of Friday night high school football games for example.

A successful attack need not injure or kill civilians. It may not even make major headlines. It just needs to demonstrate enough capability to generate sufficient public outcry to slow consumer and commercial UAV sales and deployment. Lawmakers already show a great deal of interest in responding to requests for greater regulation and the industry has demonstrated little effective lobbying power to hold off these regulations. A notable hostile use of a consumer UAV could result in regulation that would have significant impact on the civilian industry predicted to be worth $2 billion by 2020.[1]

Full text of my thesis is available here – David Kovar – GMAP 16 – Thesis

[1] B. I. Intelligence, 2016 Oct. 2, and 092 2, “THE DRONES REPORT: Market Forecasts, Regulatory Barriers, Top Vendors, and Leading Commercial Applications,” Business Insider, accessed February 15, 2017, http://www.businessinsider.com/2016-10-2-uav-or-commercial-drone-market-forecast-2016-9.